The $3.5 Million Mistake: How Suburban Living Sabotages Working-Class Wealth

Want to Build Wealth on a $60K Salary? Start Here.

Since I first moved to the New York City area, I have heard a never-ending stream of complaints about the prices of housing in the city from friends, family, and an endless stream of media talking heads. What they miss is the bigger picture of life in the city. A life powered by public transit. Here’s a hot take, buying a house or apartment in NYC is the best financial investment that a working person can make, full stop. Rethinking the notion of a house in the suburbs and two cars in the driveway maybe the only sure path working class families can take to build financial security today. Let’s face facts, if you are not driving as part of your job, your car is a financial black hole dressed up as a fashion accessory.

I have long thought about how and where a young professional looking to build wealth through real estate could start their journey. This post explores a financial path that a recent college graduate may be able to take as their first, and likely most consequential, real estate deal. We will compare three distinct New York metropolitan area living scenarios for a household with an annual income of $60K to $90K, as reasonable income assumption for a recent college graduate. Lastly, while we focus on New York City, this analysis will likely hold true in any city where public transit can replace personal vehicles.

The TLDR; the urban, car-free model, especially when combined with homeownership, provides a superior long-term financial trajectory. The significant and perpetual savings from the complete absence of car ownership, combined with a favorable property tax structure unique to New York City co-ops, create a powerful and sustainable wealth-building engine. In contrast, the suburban, car-dependent lifestyle, while attractive on the surface, is hobbled by an unsustainable dual-transportation cost burden, burden of multiple cars, and disproportionately high property taxes that erode a household's financial progress over time. Keep reading to find out how much this actually costs you.

Let’s explore three scenarios:

Urban Homeowner - Buying a one-bedroom co-op apartment in an outer borough neighborhood and commuting on the train or bus. While the initial cash for a down payment is really big, the monthly costs of ownership, including mortgage, and a maintenance fee that bundles property taxes are often lower than the total costs of the suburban model. This scenario provides the most stable and predictable path to home equity and financial security.

Urban Renter - If you are not yet ready to commit to homeownership, the urban rental model has the lowest short-term monthly expenditure. The lower financial barrier to entry creates room in your paycheck to set aside savings, creating a reserve that can be leveraged for a future down payment. However, this model lacks the inherent wealth-building benefits of home equity and is subject to the continuous volatility of the rental market, where costs can rise unpredictably. When paired with public transportation, the elimination of car expenses still outperforms the finances of the suburban homeowner

Suburban Homeowner - The suburban lifestyle, defined by a small single-family home/condo apartment and two cars, presents a deceptive financial picture. While the home's purchase price may appear lower than trendy Manhattan or Brooklyn neighborhoods, the total monthly costs become inflated by the financial burden of car ownership, including insurance, gas, and maintenance, and a separate, substantial property tax bill. Your paycheck funds two expensive transportation systems, commuter rail and personal vehicles, that are an ongoing financial liability that limits financial freedom over time.

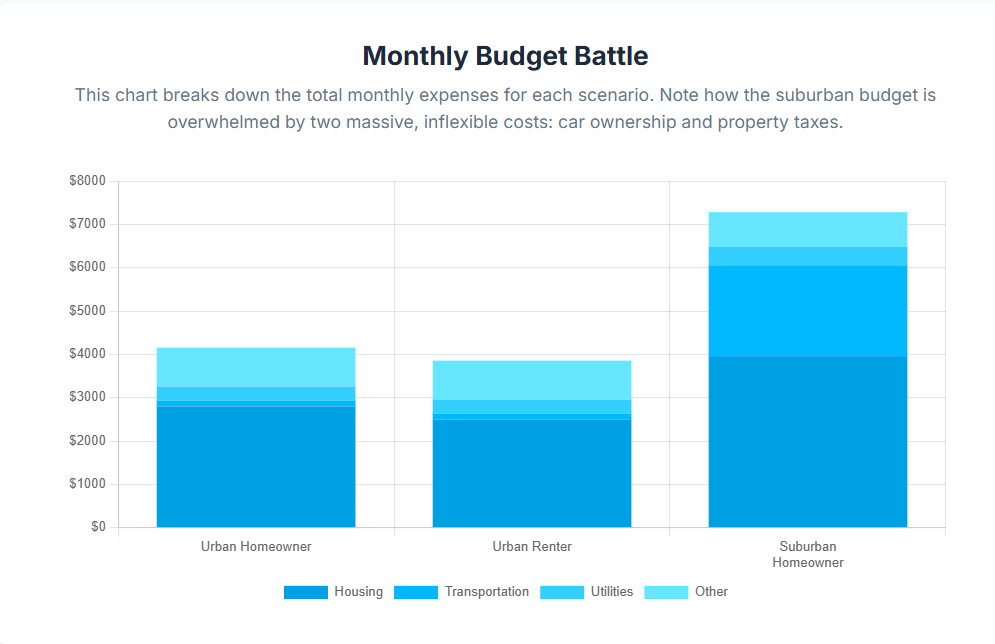

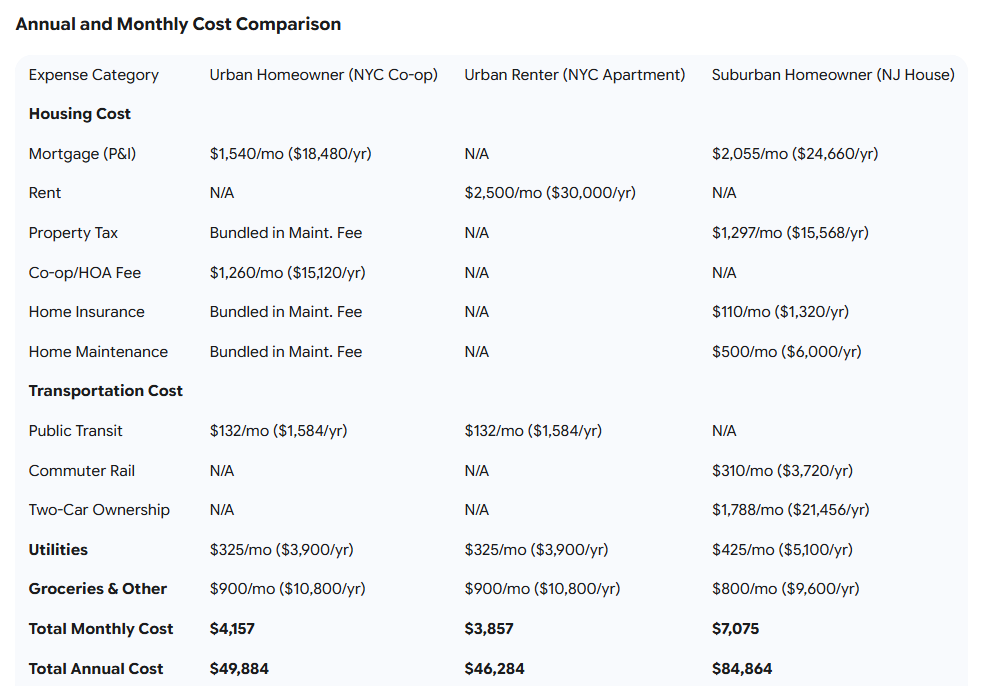

By the numbers:

Urban Homeowner - People who choose to purchase a one-bedroom co-op apartment in a working-class neighborhood within one of New York City's outer boroughs. The financial premise of this model is getting rid of your cars, removing a significant recurring liability from your paycheck.

In Queens, neighborhoods like Ridgewood and Sunnyside, with median household incomes of $76,103 and $67,936 respectively, offer viable options for urban living. While the home prices here can be high, closer examination reveals an accessible entry point for co-op apartments. In Brooklyn's 11210 zip code, which includes parts of Flatbush, listings for one-bedroom co-ops are available at purchase prices ranging from as low as $160K to $379K, with a clustering of listings around the mid-$200s. For the sake of argument, we will use a purchase price of $300K for a 700-square-foot co-op apartment, representing an attainable target for this household income.

The financial trade-off of the substantial upfront cash down payment versus the long-term benefit is the predictable cost of homeownership and the accumulation of home equity, a key component of building generational wealth. The reliance on New York City's expansive public transit network provides a low-cost alternative to car ownership, which is a key driver of the model's long-term financial stability.

Urban Renter - People who prioritize cash savings and short-term financial flexibility. The premise is identical to the urban homeowner model in terms of location and transportation: the household resides in the same outer-borough neighborhoods and forgoes car ownership in favor of public transit.

Here, we draw on median rent data from the same neighborhoods to ensure a direct comparison. In Queens, the median rent in Ridgewood is $1,654, while the average rents in Jamaica and Downtown Flushing are $2,164 and $2,202, respectively. In Brooklyn, the median rent in Flatbush is noted to be $2,048 by one source and $2,898 by another, with a general average for working-class areas hovering in the low-to-mid $2,000s. To create a realistic model, let’s use a monthly rental cost of $2,500. The monthly rent is a perpetual expense that provides no path to long-term wealth through home equity.

Suburban homeowner - The classic American dream of a detached home with a yard, situated in a commuter town with regional rail access to New York City. For those choosing this lifestyle, the primary financial assumption is the necessity of car ownership, probably two. This is not a choice, but a practical requirement of suburban life, where public transit networks are less dense and daily errands require a personal vehicle.

For this example, let’s check out New Jersey towns which are served by NJ Transit rail lines into Manhattan's Penn Station. Orange, New Jersey, is a fitting example, with typical home prices ranging from $200K to $600K and a median of $394K. Commuters from Orange can reach Manhattan in 35 minutes. Rahway, New Jersey, is another great example, with a median listing price of $515K and a commute of around 40-45 minutes into the city. For argument’s sake, we will use a purchase price of $400K for a small, single-family home to represent a realistic suburban option.

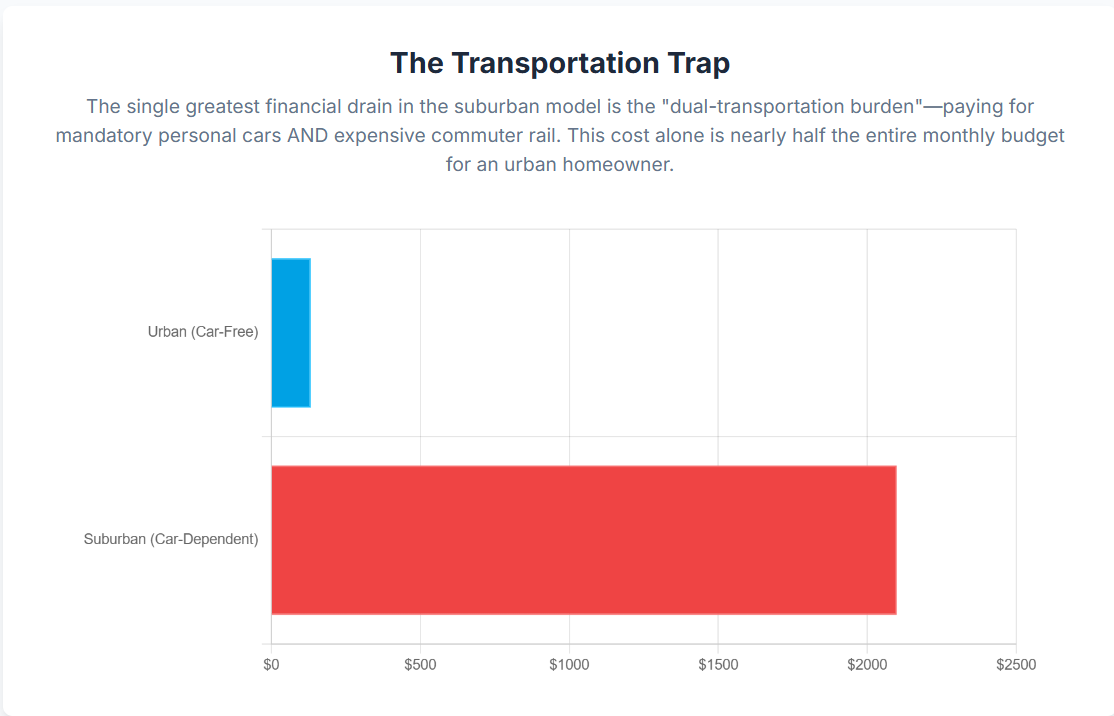

The central challenge of this model is the dual-transportation burden. A car is required for local travel, but the daily commute to NYC necessitates an additional, expensive monthly train pass for at least one household member. As this report will demonstrate, this dual-cost structure, combined with significantly higher property taxes, makes this lifestyle financially unsustainable for working-class households over time,

A financial comparison reveals a stark disparity in long-term viability for a working-class household. While the monthly costs may appear to be in a similar range at first glance, the structure of those costs determines if a family is building wealth or simply covering expenses.

The table provides a direct side-by-side comparison of the estimated annual and monthly costs for each of the three scenarios.

The biggest insight from this is not the minor differences in month-to-month costs but the vast potential for long-term financial growth in the urban model. The urban renter, with the lowest total annual cost, has the immediate opportunity to save a significant portion of their income. This surplus can be used to build the $60,000 down payment required for the urban co-op in a relatively short period, fulfilling the user's objective of using savings from renting to buy property.

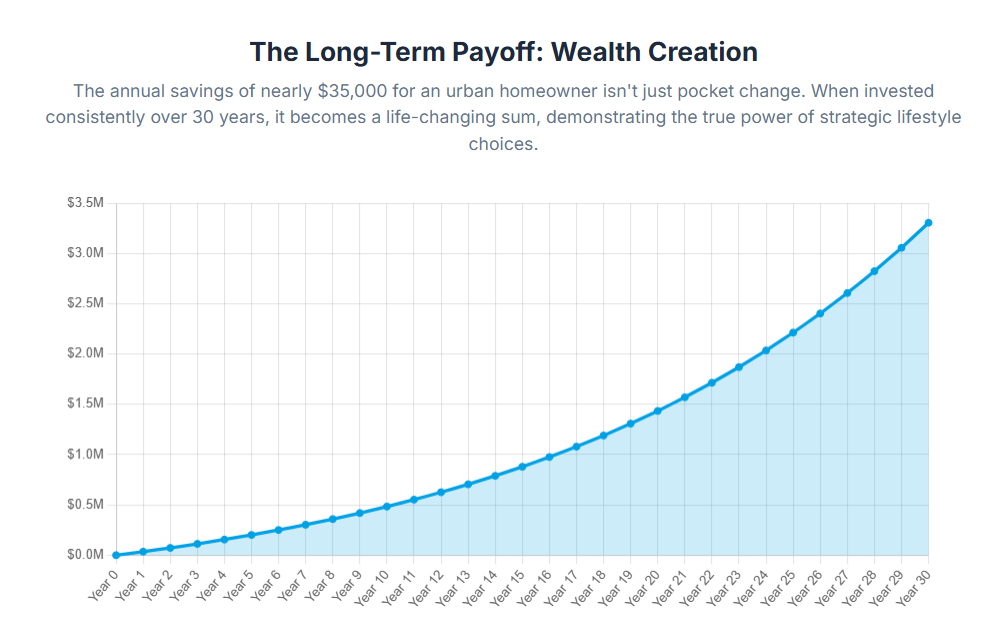

The ultimate financial advantage belongs to the urban homeowner. The suburban homeowner's total annual cost is approximately $35,000 more than the urban homeowner's. This difference is not a one-time expense but a perpetual, compounding drain on the family’s paychecks. If the urban homeowner were to consistently invest this annual difference of $35,000 over a 30-year period, with a modest annual return of 7%, the cumulative total would exceed $3.5 million. The financial compounding effect is the true power of the urban, car-free lifestyle. It is a direct and quantifiable path to financial freedom that is simply unavailable to the suburban household, whose surplus is funneled into depreciating assets and perpetual maintenance.

The urban homeowner model, by contrast, provides a direct and elegant solution to the challenges of wealth-building on a working-class income. By eliminating the single largest drain on a household's budget, car ownership, the model creates a significant annual surplus. This surplus, when combined with a manageable co-op maintenance fee that includes property taxes, positions the urban household to build home equity and accumulate wealth at a rate that is simply not possible in the suburban scenario.

So, if you're serious about building wealth on a working-class income, ditch the driveway and embrace the subway. The numbers don’t lie! Urban homeownership paired with public transit isn’t just a lifestyle choice, it’s a financial strategy. Whether you're renting or ready to buy, every dollar not spent on car ownership is a step closer to financial freedom. Your million-dollar future might just begin with an Omni Card.

Caveat: this post is a hot take designed to get people to rethink their finances and the impacts of their lifestyle assumptions. All the numbers in this post are researched approximations. As I am human, I may be wrong.

Ready for more insights from the field? I've made the expensive mistakes so you don't have to. Subscribe to get weekly strategies, real numbers, and unfiltered lessons from 25+ years of actual deals. No theory, no fluff—just lessons learned and what actually works when your money is on the line.